It is simple-minded perhaps to propose the example of Japanese tourists from the recent past as a proof of the cultural importance of travel in traditional Japan... Eyewitnesses to a world "beyond history" in the 90s, tourists from Japan cruised everywhere, armed with wonderful cameras and a desire to duplicate every "wish you were here" postcard ever created.... but with a personal touch of some loved one giving the peace sign in front of Versailles or the Kremlin or Victoria Falls.…

One may laugh at such a comparison, but the desire to record the beauties of nature, to participate in sampling local cuisine, local customs, local handcrafts of great skill has not disappeared. Spend some time with everyday TV in Japan and you will see much that resonates with that desire to explore…. From home, virtually, as well as in reality. And the brush.... through scrolls and paintings, could be seen as the virtual tool/media of the day as the computer/TV is today.

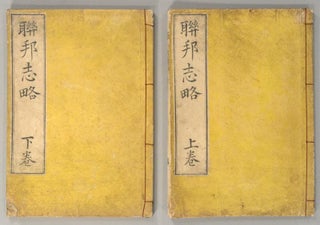

Traditional societies are often judged as to their "development" by the ease of travel within the cultural domain. The earliest and most reliable communication within the islands of Japan was by ship, as you would imagine. But the centrifugal effects of poor land communication and transportation in the mountainous land had, at least to a significant extent, been overcome by the late 16th, early 17th century period of political unification. The Tokugawa clan enacted a hostage system for less trusted grandees from the countryside that required them to spend a lot of time and money traveling from their far-flung domains back to Edo on a regular basis, the so-called Sankin Kotai...

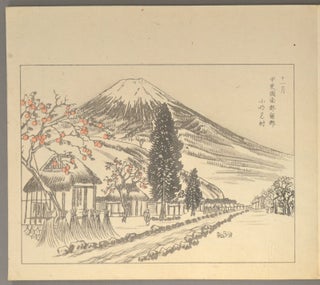

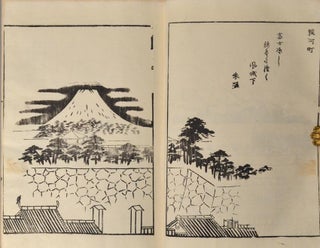

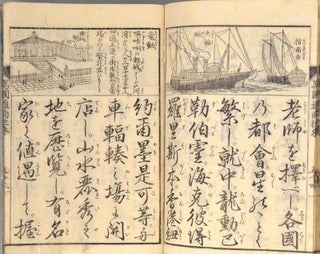

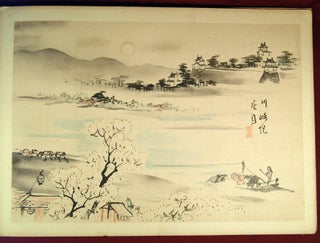

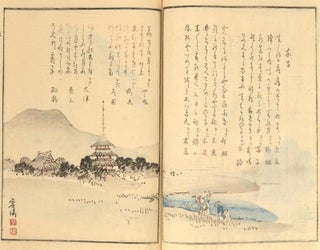

So, at least in that early Edo era period, maps and paintings of travel were often constructed for practical use. The main route, set up with 53 "stations" by the central government in the 17th century, was the Eastern Sea Route, the Toukaidou from Edo to Kyouto - some 300 miles... It would be rendered famous by Hiroshige and others in the 19th century, but Moronobu really began the genre of illustrated travel maps and guides to the Toukaidou at the end of the 17th century... His work in 5 folding volumes [TOUKAIDOU BUNKEN EZU - 東海道分間絵図」encompassed the whole route from Edo to Kyouto and gave tips such as porter rates, etc. We have handled his original printed map set in 5 volumes several times. So, when we found a lovely painted handscroll version of the Toukaidou, we realized it was obviously based on Moronobu's depiction of the route, though done decades later, probably in the mid 18th century (after an eruption on Fuji changed its profile). Moronobu may not have created the genre, but he certainly expanded and codified it. And his model was widely employed.

So, we might call that variety of travel description basically practical. After all, not just grandees were on the route. The Toukaidou was the main street of an increasingly urbanized population during the early modern period. The need for practical "direction" is implicit.... in the many guides... But, the Japanese were not unaware of the second main draw of travel records - the beauty of the route.

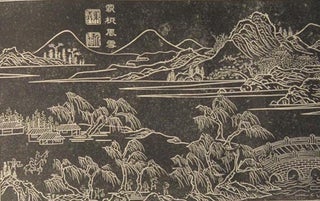

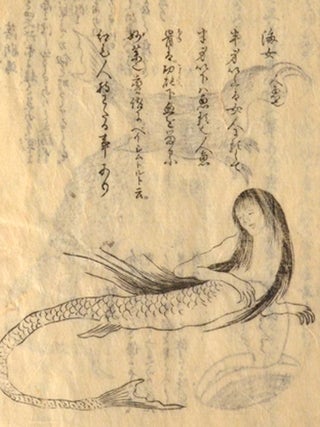

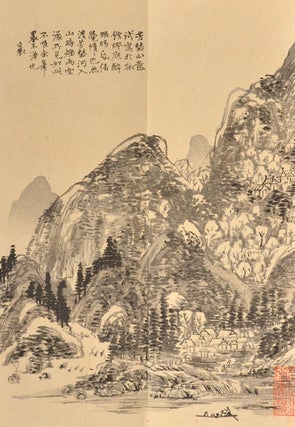

The Chinese have a very beautiful sprawling jumble of a continent-sized natural landscape. Too many beauty spots to keep track of. But eight is a lucky number, and once the eight views of lakes near Suchow were codified, there was a model to export to Japan and the rest of the cultural sphere. Eight views of Lake Biwa.... all sorts of scenic spots in Japan, domesticated and codified from Chinese exemplars and domestic numerology, as well.... 36 views of this (from the 36 Poet series), 100 views of that (from the 100 Poets series).... 6 views (also a poetical number for the 6 Poets)... All these numbers, whether of poets or mountains, all have a traditional resonance, as nature and culture are one.

OK, so, practical economic need for maps, depiction of canonical beauty spots on par with those of the ur-culture, China.... (not an attitude held today, perhaps, but China was always the parent historically, til they were not) What else? Ah, related to the second, but a bit different - destinations and routes for religious and aesthetic pilgrimages...

This pilgrimage thread is perhaps as vibrant today as it was centuries ago... I know people who have climbed Mt. Fuji, who have walked the Shikoku Island pilgrimage tour... There are 88 main destinations of the tour around the quite large island of Shikoku and many subsidiary stops, as well. The history of the route goes back to the 9th-century sage, Kobo Daishi.

There is a wonderful route from Kyoto down to the Kii Peninsula, where both Buddhism and Shinto have perhaps their holiest and most powerful pilgrimage destinations. I have walked part of that one, the Kumano Koudou... A road the Emperors were carried over in palanquin through the hills..... treacherous footing.

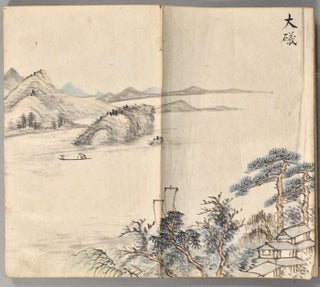

Not only believers on pilgrimage plied the pilgrimage routes... Artists gathered together to "taste" part of the road, to admire the sights, perhaps bathe in a frigid waterfall for purification.... sample the local food and drink. And write some poetry.... draw some scenery..... The use of a writing brush would later be largely replaced by the use of a camera, perhaps, but one also often sees folks sketching on their way - in parks, on trains - the brush is by no means a lost tool...

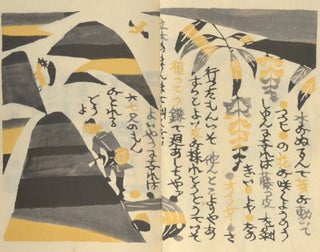

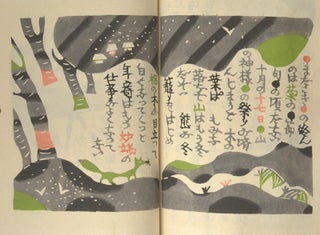

One of the most interesting examples of that genre was the woodblock printed facsimile of a work entitled JUUJUN KAGETSU-CHÔ, created in Mid-Meiji, the 1880s. The original of the work was a journal kept by the important Confucian scholar, Rai Sanyô, his mother, Rai Baishi, and his uncle, Rai Kyôhei, in the 1820s. All three were noted intellectuals - his uncle a fine painter, his mother a well-known poet. And they all were fluent with the brush... Intrinsically capable of expressions through both calligraphy and painting, the brush being the bond between culture and creativity - a bond celebrated by ink on paper.

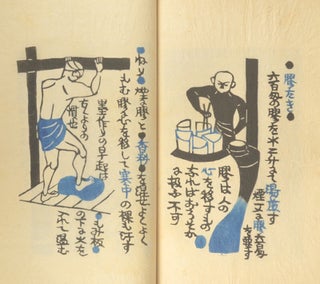

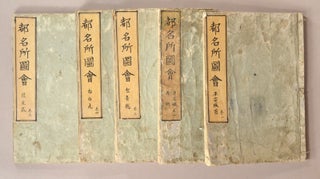

There were also wonderful gazetteers (meishoki - 名所記). The earliest of these local reports on the customs and sights of the burgeoning urban centres were such works as the EDO MEISHOKI, or the KYOU WARABE (abt Kyouto) of the 17th century. They further flourished in the 18th and early 19th century. A multitude of reports on local everything, from regional dishes to Shinto ceremonies to handmade paper or pottery specific to the region... local color, the varieties of being Japanese...

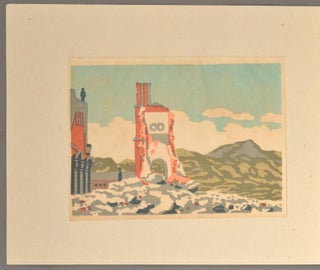

All these expressions survived the end of the old regime. The 20th century contains an avalanche of travel-related work in the arts...

There are conventional iterations of the old visual tropes during Meiji and thereafter..... Fuji, Toukaidou, The Pilgrimage routes, etc... But the source and emphasis and audience evolved to fit the times, of course.

In our brief survey of 20th-century Japanese travel books, we are concentrating on the persistence of aesthetic strands from traditional Japan, added to the new categories and media of "modernity". The artists and authors often emulated creative groupings of earlier days. The beginnings of an appreciation for the persistence of creative groups (so-called "za" 座) and art movements from pre-Meiji right up to the post-Pacific War period have developed among scholars over the last few decades. That appreciation resides mostly in Japan, it is true, but the 20th Century is slowly drawing more interest in scholarly circles outside of Japan, as well. There is much to be learned about the continuing contribution of Japan to the growth of international aesthetics before the War as well as after.

Granted that many different traditional schools were brought together with an effort to integrate certain western techniques of watercolor, perspective, etc.... in a painting genre named Nihonga in the 20th century, it is still clear that the dominant strain in Nihonga was tradition - in subject and materials and execution. The brush still reined supreme.

The Shinhanga school carried over the concept of the traditional atelier approach to the woodblock print - the cooperation of artist/designer, colorist, blockcutter and printer. But, if any strand from the past can be located for the Creative Print artists (Sousaku Hangaka - 創作版画家), it is that of the amateur ideal.... the bunjin "literati" artist...

It could be argued that the group around the famous intellectual, professor, and author, Natsume Souseki in late Meiji, which met on a regular basis was one such locus of creative efflorescence with a traditional pedigree. In the 19 oughts, the members were designers, poets, novelists, publishers, illustrators, book designers, etc., etc.... "modern" talents, "modern" roles, but their group smacked of Edo, of haikai poetry and Nihonshu rice wine.

We won't even touch (for the moment) on how such avant garde groups as MAVO might be considered as descended from tradition.....

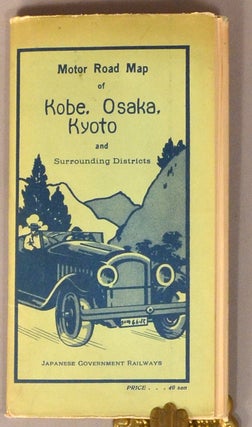

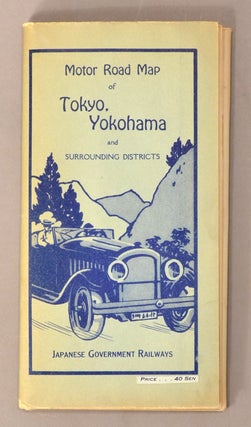

There is also a group of photograph albums, several with original albumen professional photographs from the studios that popped up all over Japan in the late 19th century. Some guides for foeign tourists as well: road maps, hotel brochures, etc. Japan has always been a tourist destination since world wide travel routes for tourists became possible in the late 19th century. The "mysterious east" tour for the wealthy Westerner often began in Koube or Yokohama....

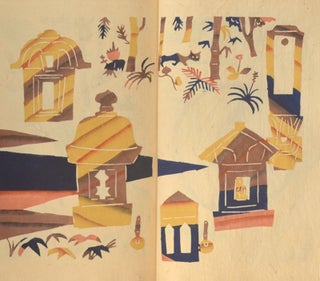

The final part of the list celebrates the wonderful group of creative print artists, scholars, and literati who explored the traditional world of folk art in 20th century Japan. Founded largely by the work of Yanagi Souetsu, he was joined by such scholar-artists as Kamakura, Serizawa, Munakata, Goto, Kyosen, Okamura - geniuses who exemplified the amateur ideal in the 20th century. They explored the countryside - finding handmade paper, local toys and pottery, metawork, a world of traditional "mingei" peoples' art they sought to discover and preserve. They created wonderful works celebrating those discoveries in woodblock and, particularly, katazome stencil... We owe them an enormous debt....

So, in conclusion, this is a glancing blow at trying to create a structure for looking at the concept of travel in Japanese aesthetics and art history as expressed in a large pile of books, scrolls, and paintings we own.. created from the 17th to 20th centuries in Japan. That said, the list which follows has all the arbitrariness of tea leaves in the bottom of a cup... Forgive my reading... Like many of the artists as artists, I profess an amateur ideal as a scholar.

So, my divisions of the list are perhaps arbitrary, Imagine distinguishing between a “meishoki” and a “zu-e”. It is often the degree of “insider knowledge” involved….

What about a “shasei” album?…. Depicting scenes on a tour of famous beauty spots or traditional pilgrimage…. Professor Scott Johnson of Kansai University named the “shasei ryokou” sketchtour genre years ago. He was concentrating on the work of the fine printer Kanao Bun’endou in the 20th Century but it is clear that there was continuity with tradition in his efforts. "Sketchtour" - Prof. Johnson's term for "shasei" - continued a genre with deep roots in the past We’ve included the Meiji printed version of such a journey of friends completed in the 1820s. But the genre probably reached a peak in its popularity in book form, often western bound book form, in the early 20th century.

You see…. Boundaries are fluid and often expostfacto… I have titled some sections of the list to reflect the cursory categorization of this preface. But be your own judge as to what fits where. And please, enjoy...

Spring is almost here!

![Item #80883 [Japanese Ephemera Collection]...](https://rarebook.cdn.bibliopolis.com/pictures/80883.jpg?width=320&height=427&fit=bounds&auto=webp&v=1530980627)